THE WHOLE TOWN'S TALKING (PT 1/3)

Anita Loos makes the move from the silent screen to the Broadway stage

“Care in seating a customer comfortably before a mirror is a very important factor in making a sale.” —Charlotte Rankin Aiken, Millinery

“If she is what they call in the theatre a ‘quick study’ this girl will learn quickly. . .”

—Lilly Daché, Lilly Daché’s Glamour Book

It would have been something else indeed to have been in Manhattan at the New Bijou Theatre, located on 45th Street and Broadway, on Monday, November 19, 1923, to see the opening night performance of The Whole Town’s Talking, the new play by Anita Loos and John Emerson.

It was the first foray on Broadway by Loos after her precocious success in silent cinema. Her husband Emerson, fifteen years her senior, had been there before and perhaps was back for less than gallant reasons. “In switching from movies to the stage,” speculates Loos biographer Gary Carey, “Emerson may have been unconsciously maneuvering himself into a position of power over Anita. Her efforts at playwriting were few and far in the past, while he considered himself ‘a man of the theater,’ much more knowledgeable about stage technique than she was. Anita thoroughly agreed—it wasn’t a contest she cared much about winning. It was tacitly understood that while she would do most of the actual writing, Emerson would be at hand to provide guidance and editorial assistance. He would also, of course, receive co-authorship credit” (84).

It was a process that had been established already in their instructional self-help offerings, How to Write Photoplays (1920) and Breaking Into the Movies (1921), and one Loos would follow later—albeit less psychologically, romantically, and financially fraughtly—with Helen Hayes in tow in Twice Over Lightly (1972). She hardly blanched at hitching her star to those more established in a given field, even if she had to do the brunt of the hauling.

The lead role of Chester Binney at the New Bijou was played by Grant Mitchell—born fittingly in Ohio, where the fictional Chester resides—who by 1923 was already a veteran of the stage. (And the son of a veteran: his father was a Union General in the Civil War; his father’s mother was the sister of President Rutherford B. Hayes.) Mitchell attended Yale, where he was an editor of the campus humor review, and went on to graduate from Harvard Law. But, being bit by the acting bug and dreaming of Broadway, he left the law to grace the stage.

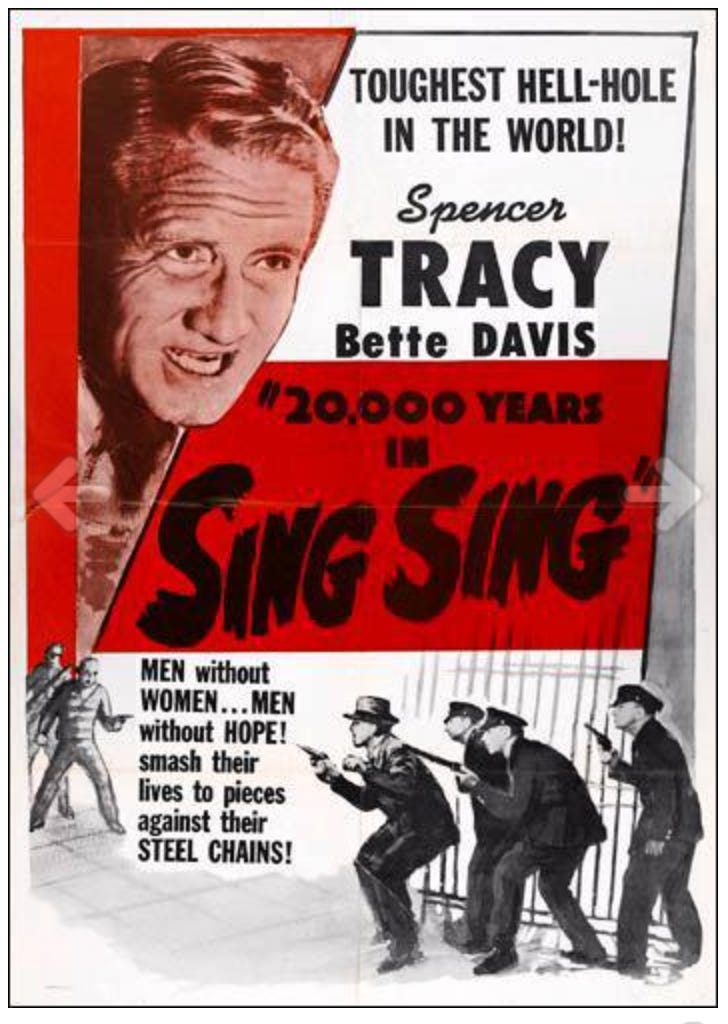

Mitchell paced the boards and plied that trade for three decades before moving to the movies, making over 125 of them between 1930 and 1948, the year he died. You might have missed him in The Bride Wore Crutches, Broadway Gondolier, The Corpse Came C.O.D., 20,000 Years in Sing-Sing, Twenty Million Sweethearts (in which he also played a character named Chester), Larceny Inc., and The Case of the Howling Dog. You likely caught him, if only glancingly, in Arsenic and Old Lace, The Grapes of Wrath, The Man Who Came to Dinner, and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. He was the kind of fellow who has a slightly familiar, not-quite-totally but almost-forgettable face—the perfect face for milquetoast Chester Binney.

If you happened to skip its significant run at the New Bijou—stretching for 170 performances, “at a time,” as Carey writes, “when 100 performances guaranteed box-office success” (85)—you could hop a train to Chicago’s Adelphi Theatre, where it ran with the original cast for six weeks starting April 21, 1924.[1] Heading back east, you could see a new batch of actors in the roles, as the Boston Stock Company put it on in that city’s St. James Theatre starting the second week of 1925. Barring that, you could travel down South if time permitted and catch it the week starting February 9 that same year at the Lyric Theatre in Atlanta, featuring their own company of actors, the Lyric Players (“America’s Foremost Permanent Stock Organization”)—but you’d have to act fast, as the cover of their playbill advertised a “Change of Play each week.”

After a lull of a year, you could wind your way back to the Windy City, where on March 21, 1926, the Studebaker Theater opened a performance of Pair O’ Fools, a “Farce, with song and dances” based on Loos’s play. “What was funny in ‘The Whole Town’s Talking!’ is, after two years, still funny in the loose make-over,” writes the critic on the scene of the Chicago Daily Tribune. “The farce, in outline and in the comic details of its second half, is much as it was when Grant Mitchell, Frank Lalor, and Miss Catherine Dale Owen performed it at the Adelphi.” Much as it was, but different; for, apart from the songs, “the divertissements of the new version consist of dancing by sixteen girls of the type known a generation ago as ‘pony.’ They are young, sprightly, and nice-looking” (33).

The Studebaker stay was a short one for the company run by Bill Kolb and Max Dill (the latter playing Chester, here renamed “Rudy Valentino”), for on the same day that the Chicago Tribune published its review, the Los Angeles Times had a preview of the same revised version: “The Mason Theater seems to be the laugh headquarters for the time being, where Kolb and Dill are playing their annual engagement in Los Angeles, presenting for the first time ‘Pair O’ Fools.’ Anita Loos and John Emerson, a tried and successful pair of collaborators in writing stories for the screen, are responsible for the book, and Byron Gay composed the lyrics and music.” The “‘Sweet Sixteen’ Dancing Girls, a group of young beauties” (22), are similarly mentioned, as of course you’d expect them to be.

After all that, a voyage across the pond to London in time to arrive by September 7, 1926 and possession of a ticket to the Strand Theatre would give you entrée to the opening night of the original play’s West End incarnation. By then Gentlemen Prefer Blondes had been making its splash as a novel, as is implied in the opening paragraphs of a contemporary review of the show by Mabel Howard in a weekly rag called The Sketch. Howard’s whole assessment, which considers the new production in terms of the fashions it displays, introduces the play through Blondes-colored glasses: “Anita Loos is the name about which the whole town’s talking at the moment, and in her play of that name at the Strand Theatre the perfect blonde, although in this case not preferred by every gentleman, at any rate wears frocks which will surely be coveted by every woman” (583). Thus hovers over the play the spirit of Lorelei Lee in London, even though in Blondes a section is headed “London Is Really Nothing” and Lorelei confesses to her diary that “everything is much better in New York, because the boat comes right up to New York and I am really beginning to think that London is not so educational after all [. . .] London is a failure because we know much more in New York” (33).

Apparently unoffended, The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News noted the play’s appearance at The Strand by also raising the recent specter of the novel: “Miss Anita Loos, who wrote Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, is partly responsible for The Whole Town’s Talking [. . .] The story sets out to show that ladies prefer gentlemen with purple pasts[.] [It] lacks the delicious satire which gave such piquancy to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, but it is such good fun that it is likely to set the whole town laughing before the last of it is seen in the West End” (771).

A week later the same publication had a more extensive accounting by “Our Captious Critic,” who was less forgiving: “If the whole town’s talking, it’s because this farce doesn’t grip it enough to stop its clack.” Blaming the play’s “relative tameness” on “indifferent casting” and “inexpert authorship,” the captious critic is most impressed by the final scene in which Chester dangles from a chandelier, a scene that is optional in the stage directions—“If the mechanical contrivance for this effect is not available CHESTER may be sitting on top of the bureau up at back L.C., and in this there will be no loss of effect” (77)—a claim undone by the captious critic’s faint praise. He was less impressed by the lack of “verisimilitude” (which “even in farce you must have”) and by the performance of the aforementioned Catherine Dale Owen as Letty (now “Norma”) Lythe: “She served to prove that, though gentlemen prefer blondes, in the theatre they only do so when they can act. Miss Ruby Miller is now in that part” (14).

The Sketch also covered the play with its own captious (this time non-fashion) critic, “The Clubman” (aka “Beveren”), who similarly thought less-than-highly of Owen, an actress who, although “a beautiful girl,” “wasn’t well made-up on the opening night of the play. She looks many times as beautiful off the stage as on”—a propitious state of affairs, as she apparently wasn’t on it for long once Miss Miller took over the role. The Clubman also noted the interest in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes in England as a spur to the production and used it to draw a trans-Atlantic distinction: “The people who brought over the Anita Loos play are bent, naturally, upon striking the iron while it is hot, letting us see what Miss Loos can do as a dramatist while the whole town is talking about her book, ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.’ The Americans are better than we are at this follow-hard-afoot upon a first success [. . .] Well, Miss Anita Loos’s play is not as good as her book” (502). It is a slightly dyspeptic if fair enough assessment, seeing as how Blondes turned out to be an all-time classic and Talking was merely Loos’s dramatic debut.

Yet as you can see, even if it didn’t reach the satirical heights, it was hardly unproduced, and what’s more it was highly mutable. The American penchant to “follow-hard-afoot” upon Loos’s newfound if relative success as a playwright found its Hollywood manifestation when, just a few months later, on Boxing Day of 1926, the big-screen movie version debuted, starring Edward Everett Horton in the Chester Binney role and Delores del Rio in the role of the movie star ingenue—renamed again, this time from Letty Lythe in the play to Rita Renault for the film.

Perhaps this perpetual renaming was due to the fact that professional courtesy urges discretion. Loos had suggested as much in Breaking Into the Movies, even if she violated the advice in her naming of Lythe in the first place. For the name “Letty Lythe” was inspired by that of sultry film star Betty Blythe, whose movies included 1921’s The Queen of Sheba (among 118 others), and one of whose first theatrical roles was in a play called So Long Letty. As the Jewish Advocate put it in previewing Talking before its Boston debut, “To those who follow the doings of Hollywood it will be easy to guess which screen star the authors had in mind when they created the character” of “Letty Lythe, the movie-vamp” (4).

Another movie version came in 1931, this time titled Ex-Bad Boy. It starred Robert Armstrong as Chester and Lola Lane as Letty Lythe, who in a cascading plethora of L’s was now renamed “Letta Lardo,” which was meant to chime with “Greta Garbo.” The most Garbo-esque member of the cast, however, was not Lola Lane playing Letta Lardo (erstwhile Letty Lythe), but Jean Arthur playing Ethel Simmons, Chester’s true love interest. Arthur, who starred in dozens of films—her last was the Western classic Shane in 1953; Ex-Bad Boy was already her 61st—“recoil[ed] from interviews” and was a private person off screen who “avoided photographers and refused to become a part of any publicity.” A 1940 Life magazine profile claims that “[n]ext to Garbo, Jean Arthur is Hollywood’s reigning mystery woman.”[2]

Also interesting for aficionados of old Hollywood is the fact that the soon-to-be jilted beau that Ethel brings home is played by Jason Robards, Sr. And while we’re on old Hollywood, it is worth mentioning for clarification that in 1935 came a second movie titled The Whole Town’s Talking, this one directed by John Ford and starring Edward G. Robinson—although, being about a murderous doppelganger, it has nothing to do with the Emerson-Loos production. (Nothing, that is, except the fact that one of its working titles was Passport to Fame, which would fit the Loos play to a tee, and also involves someone pretending to play a person one is not.) Jean Arthur starred in that one too.

Twenty-five years later came perhaps the play’s most unexpected, inventive manifestation on film, 1960’s A Rumour of Love, or إشاعة حب in Arabic. This Egyptian production, directed by Fatin Abdel Wahab, stars Omar Sharif in the Chester Binney role (styled here as “Hussein”), with the Letty Lythe character now named “Hind Rostom”—and played by Hind Rostom, the Egyptian actress and sensual star of numerous films. This playful touch of meta-casting must have been a self-referential delight to contemporary audiences already familiar with Rostom as the “Marilyn Monroe of Egypt” and the “first lady of Egyptian cinema,” a celluloid seductress playing herself against heartthrob Sharif, here cast against type as a bland nephew provoked by his uncle into using Rostom’s sexy fame to change his status from boring Hussein to Hussein with a playboy past.

Any man might be so changed in being linked to the headstrong and beautiful Rostom, who maintained her fiery sense of self-worth well past the days of her starring roles, turning down late in life a million Egyptian pounds to write her autobiography and rejecting in her seventies her nation’s State Merit Award in the Arts by remarking, “There’s only one Hind Rostom in the Middle East. . .[and] it’s not appropriate to honor me after years of honoring people who are less than me[.]”[3] One who wasn’t less than Rostom was her female co-star, Soad Hosny, the “Cinderella of Egyptian cinema,” who played “Samiya” in the Ethel role, just one of over ninety parts that she rendered on the silver screen.

From Broadway to the West End, from Chicago to Atlanta and back, from the movie palaces of dusty, emerging Hollywood all the way to the sands of ancient Cairo . . . imagine that! And all of these iterations one wishes to have watched in real time. Yet of the multitudinous productions of Loos and Emerson’s comedy of manners and mix-ups, the version I would most like to have seen is the one put on by the Dedham High School Class of 1937 in the George F. Joyce Auditorium on Friday evening, April 30, 1937, in Dedham, Massachusetts. . . .

—Andrew DuBois

[1] Two Aprils later another Loos-Emerson collaboration, The Fall of Eve, would be staged at the Adelphi, after having premiered in 1925 on Broadway. As if taking the finale of The Whole Town’s Talking and stretching it, the action involves jealousy over a man’s commingling with a movie star, although this time the jealous party is a woman. The critic for the Chicago Daily Tribune was unimpressed and sussed out some borrowings from other sources: “John Emerson and Miss Anita Loos, as they did with The Whole Town’s Talking, ask credit as the authors of the play, which is a farce with numerous indications of Continental origin.” (Shaw’s Man and Superman is mentioned, as are plays called The Conquerors and Sleeping Partners.) The cast, writes the critic F.D., makes of it whatever is possible, played “with as much of froth and spirit as can reasonably be expected[.]” The lead actress, “Miss Risdon,” is singled out for “doing astonishingly well with Eve,” a character F.D. refers to, in an interesting bit of period diction, as a “mattoid,” which is a person who displays eccentric behaviour approaching the psychotic. Perhaps it took a veteran like Elizabeth Risdon to pull off Eve, “in view of the part’s having been written in one key, and its calling on the player to do one thing over and over—and over” (27). The Fall of Eve was made into a movie by Columbia Pictures in 1929, with Gladys Lehman writing the screenplay.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Arthur